We're A Hit

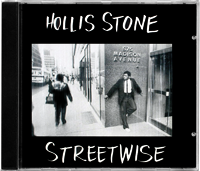

Thirty-one years later, we're a hit. For reasons both inexplicable and

amusing, Streetwise, my first studio effort, somehow found its

way out of the living rooms of the perhaps two dozen people who

owned a copy and into dance clubs in Germany and France. I have

absolutely no idea how that happened, or how this little private

pressing has become a bona fide collector's item. What I can

tell you is I field nearly a dozen inquiries every week asking

if copies of the original vinyl release are available. So much

so that I've created a form letter response, telling the same

story of the extremely limited supply of sealed, shrink-wrapped

copies packed in boxes which were destroyed when my basement

flooded. The only copies I know to exist belong to the band

members themselves, at least two of whom--R&B producer Dinky

Bingham and The Voice house band vocalist Michael Hammond (who

was age eleven when we recorded this) --have gone on to

successful music careers. I myself own only one copy of the

original vinyl, and would happily purchase another from

collectors' resources if I could actually afford it. Prices have

thus far ranged from mid-three hundred to $1,429 per copy. And,

no, I don't get a royalty.

I find it enormously amusing and amazing all at once. The value

is surely in the scarcity of the vinyl first pressing and not in

the music itself. I sing a lot like a wounded moose and, with

the possible exception of the late brilliant funk bassist

William Wallace and the eleven-year old Michael (both praised in

correspondence sent to me and internet postings), the music is

of questionable value and the recording, on one-inch Scully

eight track, is iffy at best. I did spend real money on the

mastering from Bernie Grundman, whose company has mastered

countless classic LPs, and MasterDisc, one of America's

preeminent vinyl producers, created the master cylinder and

manufactured the discs.

Offering digital versions of the album would be iffy because the

only source files I have left are 292 kb ATRAC compressed

MiniDisc, and I omitted several tracks because they really were

just that bad. I suppose MasterDisc still has the

original master cylinder lying around somewhere and film for the

jacket, but, seriously, I can't imagine a second pressing of

this, a first effort by a group of high school kids.

For this 2000 compilation, sent to the original band members, I

used some alternate takes from the original Streetwise project,

stuff that exists now only on cassette and on the custom CDís

created for them, so

there really isnít any way to clean those tracks up. Also, Iíve

juggled the sequence of some things, looking to tell more of a

story than present a true anthology.

Love Letter #2 was never included on an official project, but

was kind of an afterthought. We had a little tape left on the

1982 White Soul album project, so I sat at the piano and warbled

my way through this little ditty, a musical note to Karen. I was

really uncomfortable playing and singing at the same time, but

this wasnít supposed to be polished and was really more of an

apology to her for spending so much time on the second album.

Iíve started the compilation with it because, looking over this

work, the core themes are my obsessions with women and God. The

cheery optimism of Love Letter #1 contrasts sharply against the

grim fatality of Chapter 4ís If I Should Perish (Love Letter

#4), this compilationís closing number, and I think they make

good bookends here.

The prayer invocation, Youíre The One, is our grace before

serving up the meal. Thereís some really fine Fender Rhodes here

by John Parker, who was constantly underrated, existing largely

in the shadow of Dinkyís pyrotechnics. I think we took this

live, with me standing in the drum booth while John played in

the studio.

1982ís Sorry To Say was, perhaps, the most successful piece of

studio music we did, Largely thanks to Dinky and John who

brought this Los Angeles smooth laid-back arrangement to an

otherwise forgettable amalgam of Shame and We Are Family. Dinky

hated his solo, a ripping 3-1/2 minute jazzy thing I copped off

of a Rolls Royce tune. I just didnít have the cash to let Dinky

go back and redo it, and, to my then-untrained ears, the solo

sounded fine. It still does, though I can see why heíd want

another shot at it.

We went in at about 10 PM to record Sorry..., and emerged about

7 AM. Yanick and Florence, the twins, worked at a cookie shop on

Queens Boulevard, and we headed over there for free cookies. I

was driving a rental car a friend rented for me because I didnít

have a driverís license. Neither did Dinky, who had been driving

for years without one (he was 15 or so when he started; I think

Dinky was about 17 or 18 at this time). Dinkyís example actually

inspired me to start driving without a license.

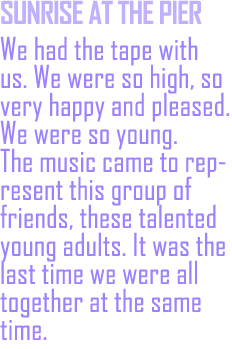

We had the tape with us, and we were so high, so very happy and

pleased. We were so young. The song came to represent this group

of friends, these talented young adults. It was the last

time we were all together at the same time.

New

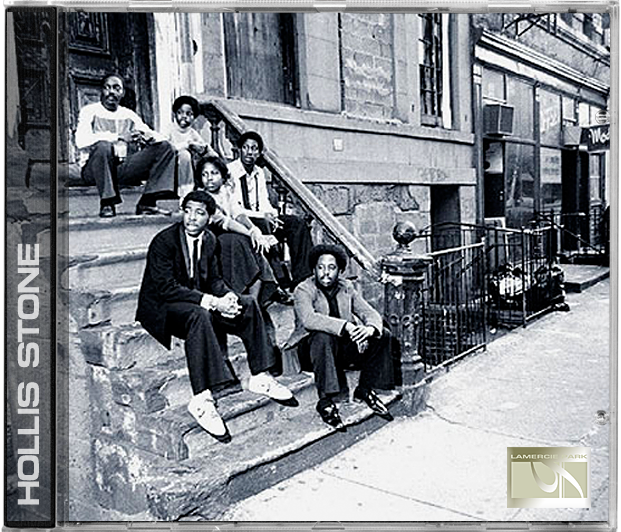

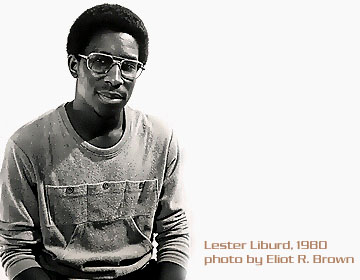

Witness:

Original cover art shot

October 25, 1980, 7:30 AM:

Tyrone, Michael, Lester, Debra, Hollis, William Missing: Gene, John, Milton, Pearl, Derek.

Photo by Eliot R. Brown. Art was scrapped after Debra left the

group.

Frenemies

William Wallace, a pal from high school, holds a special place

in The Story. When I was 15 or so, William and I formed a group

called New Witness that eventually grew into a 8 or 9-piece band

with a 25 voice choir. All young adults, all spirit-filled and

gravely serious about doing Godís work, rehearsing in Williamís

basement under the spiritual guidance of his wonderfully

anointed mother Betty, whom I bless God for having brought into

all of our lives.

William, a gifted bass player, had control issues and insisted

on being in charge, the boss, head guy. I was the bandís

manager, saxophonist and lyricist, writing over Williamís tunes

(many of them very, very good, and William was only around 15

years old). Iím sure William always knew

heíd be a star. I certainly thought he would. He was my friend,

my family. We dreamed Big Dreams together.

William threw me out of New Witness over differences in

interpretation of scripture. I was a bit incredulous that

William, as Paul McCartney, would toss Lennon out on his ear

because he says to-MAY-to and John says to-MAH-to,

but that was

pretty much what happened. I was dismissed, and the band

dissolved a few months later.

I really donít remember why I recruited William for the

Streetwise project, but I seem to recall it had something to do

with proving to him I held no hard feelings toward him. But

this was definitely my project, and William braced against

taking my direction. I ended up naming him co-producer or

something, but he wasnít nearly as available for those kinds of

tasks as the credit suggested.

I really donít remember why I recruited William for the

Streetwise project, but I seem to recall it had something to do

with proving to him I held no hard feelings toward him. But

this was definitely my project, and William braced against

taking my direction. I ended up naming him co-producer or

something, but he wasnít nearly as available for those kinds of

tasks as the credit suggested.

A decent person, fun to hang out with and a giving person

socially, William was what I would describe as a selfish

musician. Most musicians are selfish people, interested

primarily only in their own work and own projects. William

played his own tunes, like Mr. Ugly, very well, but played my

tunes with a kind of marginal enthusiasm. Mr. Ugly is William to

me, a pivotal figure in The Story, and a source of conflicting

feelings of loyalty and resentment.

Mr. Ugly also has a noise track over the music, where the band

stood around talking. This was a crude homage to Tom Brownís

Funkiní For Jamaica, but its role in this compilation is to

bring those people back to life. Those happy peopleó William,

Derek Burch, Milton, John (ďYeah, maybe I got old sneakers but

you canít play no ball, nigger!Ē), and at center stage, James

Crockett.

James wasnít in the band. He was my best friend and adopted

brother. He was trying to date Yanick in high school, and he was

the one who brought the twins into the project. James, like

Michael Hammondís ubiquitous bodyguard Dexter, became a kind of

hanger-on, only, here, on this tune, he became part of the band,

making the track sing simply by being himself.

Dexter, by the way, was sent along with 11 year-old Michael to

make sure, I guess, that we werenít sickos out to exploit the

kid. But, after a few sessions, Michaelís mother knew we were

okay, and Dexter became more of a band mascot than Michaelís

bodyguard. I remember roaming Brooklyn in the after-hours with

the band, feeling perfectly safe because we had Dexter with us.

We were musicians, not tough guys. James was a tough guy. Dexter

was a tough guy. And, between Dexter and James, nobody was going

to get stupid with us. Weíd wander out at 2AM looking for food,

or take the subway over to the Village or whatever we wanted to

do. It was a really great time with really great friends.

Dexter, by the way, was sent along with 11 year-old Michael to

make sure, I guess, that we werenít sickos out to exploit the

kid. But, after a few sessions, Michaelís mother knew we were

okay, and Dexter became more of a band mascot than Michaelís

bodyguard. I remember roaming Brooklyn in the after-hours with

the band, feeling perfectly safe because we had Dexter with us.

We were musicians, not tough guys. James was a tough guy. Dexter

was a tough guy. And, between Dexter and James, nobody was going

to get stupid with us. Weíd wander out at 2AM looking for food,

or take the subway over to the Village or whatever we wanted to

do. It was a really great time with really great friends.

Daddy was a shot at my father, whom I have never met. When I was

10 years old, I used to sing a lot like young Michael Jackson,

so I recruited Michael Hammond, who sounded a lot like I did at

that age, to play my role in The Story, while I sang the part of

the grown-up me. I canít remember how I met Michael, except that

I had heard of him before I actually heard him, and was

introduced to his mother and worked things out with her before I

was formally introduced to this kid. Michael became a kind of

protťgť, which I now find a little laughable, considering I

didnít know what the heck I was doing.

Lester Liburd hated the drum pattern I wrote for the song. One

of my oldest friends in the world (we met at age 3 and our

friendship began on tricycles), Lester had a way of shooting me

this sarcastic, ďYouíve gotta be kidding me!?!Ē look. Iím so

used to hearing the pattern now, itís hard to remember his being

so up in arms about it.

The Blessing was a song written for Karen, a girl I met when she

was 17 and living in Atlanta (long story). It had a bizarre key

shift on the chorus that kind of ruined it, I think, going from

A flat minor to B flat minor. Debra sang the song, but later

dropped out of the project under religious conviction against

secular music. The version that appeared on the album was a much

slicker mix with Pearl Bates performing the female lead. I

didnít include that version here because, with each consecutive

re-make of the song we lost more and more of its soul. Debraís

original lacks much subtlety, but the honest, rawer emotion is

much more beguiling, I think.

The Blessing was a song written for Karen, a girl I met when she

was 17 and living in Atlanta (long story). It had a bizarre key

shift on the chorus that kind of ruined it, I think, going from

A flat minor to B flat minor. Debra sang the song, but later

dropped out of the project under religious conviction against

secular music. The version that appeared on the album was a much

slicker mix with Pearl Bates performing the female lead. I

didnít include that version here because, with each consecutive

re-make of the song we lost more and more of its soul. Debraís

original lacks much subtlety, but the honest, rawer emotion is

much more beguiling, I think.

Prisoner of Madison Avenue was written for Karen. I was then and

am now a workaholic. I was also seriously enamored of this

cheery Billy Joel pop style (I think I had just gotten into

Allentown or Glass Houses) and was seriously into pop formula.

Dinkyís wonderful jazz riffs on Fender Rhodes were something I

could not fully appreciate than, but now I marvel at the then-15

year-old kid. I hated Tyroneís solo. He was a great guitar

player but he couldnít solo. Then again, neither could I.

Mansion In The Sand was my attempt to build a better vehicle for

Michael, who was great little trooper. I wanted something on

side 2 for Michael to shine on. I still like the song, in spite

of its minor fifth Hollywood Game Show chorus. I included the

version with the twins featured on backup because the harmonies

are stronger. Dinkyís organ dominates the track and we played

too fast, yielding a kind of runaway train experience.

Inner City Sound:

October 1980: Debra, Tyrone, Pearl (seated) Hollis, Milton, Gene

Cropped: Lester (on drums), William (on Bass, far right). Photo by Eliot R. Brown

A New World

Elegy was something God inspired at some point during this

project. A somber and grown-up observational treatise on

Christians and Christianity, I liked it for its funereal pallor

and opted to play my own wretched piano for the raggedness of

it, rather than let a slick guy like John or a chops guy like

Dinky play it. Itís a truly morbid song that flaunts its wannabe

intellectual fakery at every bar, ending abruptly and

unfinished. Man, I thought I was something.

The Bridge was the one song I used from Williamís and my New

Witness Band. I really liked the song, and Williamís playing

here, as on Mr. Ugly, was superb, probably his best on the

album. I used an alternate take here, one with Debra and Michael

singing in a kind of cheery farewell chorus line. We lost this

version when we lost Debra (she asked we not use any of her

tracks on the album), but this is, to me, the superior

interpretation of Williamís song.

Just Friends was a vignette written to Karen. I think we broke

up or were about to break up, I canít remember. Thereís actually

a whole long-winded song behind that, but I wasnít interested in

recording it.

Journey came about during one of our endless jam sessions. I

just kept playing this little ditty Dinky put on the end of The

Blessing, and William improvised a surprisingly country western

riff over it. It was an unexpectedly Easy Listening bit of

business for this funky crew. I was nervous playing the piano

part, hoping people would not notice that it wasnít Dinky. I

also dubbed in the semi out-of-tune MiniMoog lead line. Iíve

included this reprise here as a kind of coda to the first

project as we transitioned, 9 months later, into a whole new

world.

It was Mike Theordoreís world. Theodore had just taken over The

Daily Planet, a rehearsal studio on 30th Street in Manhattan we

rented from time to time, and upgraded it to Planet Studios, now

one of New Yorkís top studios. 24 tracks, huge rooms, grand

piano, Prophet V, and Mike worked a deal with me to buy blocks

of time at an unheard of $75 an hour. Our production values went

through the roof as we began the second album, White Soul, which

followed my vision of some amalgam of Gil Scott-Heron and

Prince.

It was Mike Theordoreís world. Theodore had just taken over The

Daily Planet, a rehearsal studio on 30th Street in Manhattan we

rented from time to time, and upgraded it to Planet Studios, now

one of New Yorkís top studios. 24 tracks, huge rooms, grand

piano, Prophet V, and Mike worked a deal with me to buy blocks

of time at an unheard of $75 an hour. Our production values went

through the roof as we began the second album, White Soul, which

followed my vision of some amalgam of Gil Scott-Heron and

Prince.

Have You Seen My Girl? was, oddly enough, inspired by Yanick.

Not in the sense of any true longing for her (we were completely

platonic in those days), but in the sense that Iíd been sent

searching for her once, and ended up wandering around down near

the pier trying to find her while she was trying to find a

bathroom or something. I wanted a bubblegum pop song for the

project, much like Prisoner of Madison Avenue. I was still

seriously into bubblegum, and I wanted the new album to have

some resonance with the old. Again, Dinky provided jazz riffs on

the break in the middle, playing over Derek Burchís bass. I

think, by now, William and I were kind of politely avoiding each

other, and I wanted to keep personnel to a minimum, going for

the severe Prince sound of those days. Derek pulled double duty

on bass and guitar.

The punk-inspired Join The CIA was just me being self-indulgent and riotously

cynical. I guess the song worked on some level, but I edited it

to just Michaelís parts here. Mike Theodore put a phase shifter

on Lesterís hi hat, giving it a metallic clanking sound, to give

the otherwise bald track a little something to run off of.

Same To Me was my first attempt to be Prince. Even as I recorded

it, I was humiliated by my laughable attempts at falsetto.

Eighteen

years later, it now sounds like a parody, almost a cool in-joke.

But I was very serious. I think I skipped that song every time I

played the demo. In fact, I think everyone did. I played drums

myself because I was looking for an edgy, amateurish strippy

sound, like Prince on Dirty Mind, and I knew if I asked Lester

for that he would give me The Look.

I also played drums on

White Boys for much the same reason. No

drummer I knew of could get it quite sucky enough. I also

recruited Larry Hama, my mentor in comics, and Danil Dreger, my

mentor of sorts in studio recording, to perform dueling

Stratocasters. This worked marginally well, but the two guys

didnít really gel, and I realized it probably would have been a

better idea to get Danilís bandmate to play with him, or get

Larryís bandmate to play with him; people they knew and could

easily mesh with. White Boys holds up pretty well, I think, as a

song designed to sound like a high school garage band.

I also played drums on

White Boys for much the same reason. No

drummer I knew of could get it quite sucky enough. I also

recruited Larry Hama, my mentor in comics, and Danil Dreger, my

mentor of sorts in studio recording, to perform dueling

Stratocasters. This worked marginally well, but the two guys

didnít really gel, and I realized it probably would have been a

better idea to get Danilís bandmate to play with him, or get

Larryís bandmate to play with him; people they knew and could

easily mesh with. White Boys holds up pretty well, I think, as a

song designed to sound like a high school garage band.

Drag Me Away came out of two specific influences: The

Temptationsí Masterpiece, which was producer Norman Whitfieldís

homage to himself (including a huge, messianic portrait of

himself on the albumís back cover) and a song that drones on for

nearly six minutes before any of the Temptations actually sing,

and B-Movie, Gil Scott-Heronís seminal work of biting social

commentary. Regrettably, I was no Gil Scott-Heron, and I

certainly was no Norman Whitfield. But Drag... dragged on for

more than ten minutes while I whined and complained.

One minor note: while mixing Sorry To Say and Drag Me Away, Mike

Theodore spent two full hours listening to Lesterís kick drum,

while I writhed on the sofa in the control room, counting up the

bills on the studioís still-running meter. When I asked him what

on Earth he was doing, Mike looked at me and said, ďAnything

worth doing is worth doing right.Ē And he was right. No point at

all in spending twenty-five hundred dollars and ending up with a

crummy tape.

Mike did a superb job and had lots of patience with me, someone

who had not much clue what he was doing, and who spent a fortune

recording songs no one wants to listen to.

Christopher J. Priest

January 2000 UPDATED OCTOBER 2013

Home | Blog | Projects | Comics | Rants | Music | Video | Christian Site | Contact

Unless otherwise specified, Copyright © 2013 Lamercie Park. All Rights Reserved.

TOP OF PAGE