|

|

Of course, that's never gonna happen.

Why? It’s been done to death. But it’s the kind of ending that

always works and is utterly satisfying: a glimpse into happy

endings for our heroes.

I’d heard so much about this show while I was writing Black

Panther for Marvel. Many readers compared Panther to the West

Wing, a show I had never seen. I tried catching it a few times,

but it was on Wednesday, a night I almost never watch TV. But I

did decide to take a flyer on WW when the DVD box set came out.

It took me a few episodes—I really wasn’t impressed by the

pilot. It seemed very Sports Night—a smart workplace dramedy—and

the show was clearly Rob Lowe and Moira Kelly’s vehicle. My

interest in it didn’t really pick up until Lowe and Kelly became

regularly upstaged by the brilliant Richard Schiff (Toby) who,

seriously, owns every scene he’s in, and the simply dazzling

Allison Janney (CJ), who took stacks of script pages and

turned them into riveting, hairpin turns of oratory while being

chased through the West Wing halls by a steadicam. It took me a few episodes—I really wasn’t impressed by the

pilot. It seemed very Sports Night—a smart workplace dramedy—and

the show was clearly Rob Lowe and Moira Kelly’s vehicle. My

interest in it didn’t really pick up until Lowe and Kelly became

regularly upstaged by the brilliant Richard Schiff (Toby) who,

seriously, owns every scene he’s in, and the simply dazzling

Allison Janney (CJ), who took stacks of script pages and

turned them into riveting, hairpin turns of oratory while being

chased through the West Wing halls by a steadicam.

I’d wait, impatiently, through the Mandy (Kelly) scenes waiting

for just a glimpse of CJ or Toby. And, a good an actor as Lowe

was, he really wasn’t selling it the way these other folks were.

Perhaps creator/writer Aaron Sorkin just never got the pulse of

Sam Seaborn, but I also think a relationship develops between an

actor and his/her role which, in turn, informs the writers. I

think Schiff’s performance inspired the writers to write more

towards the types of things Schiff was getting at, which in turn

inspired Schiff to flesh Toby out that much more. It’s possible

Lowe never had much of a breakthrough with Sam, and thus Sam

didn’t really evolve much from the pilot until his exit in

Season Four (Sam runs for Congress, loses, and, inexplicably,

never returns to the West Wing and is never mentioned again).

It’s possible Lowe never fully engaged with the WW because the

show was supposed to be his vehicle. Instead, he was

overshadowed, immediately, by Schiff and Janney and the

wonderful Bradley Whitford (Josh), and the emergence of film star

Martin Sheen as a major character more or less sealed the deal.

The show became an ensemble, with Sheen as anchor, whereas it

seemed designed to be a workplace dramedy about Seaborn and his

pals, with Sheen making only the odd guest appearance as the

president. I’m, assuming that, at the time, nobody actually

thought Sheen would be available on a weekly basis, but Sheen

surprised everyone by agreeing to do TV (which has now become a

trend; film stars returning to television). It’s possible

Sheen’s elevation to regular star, pushing Lowe (whose credit

always came first in the title sequence) into the ensemble,

disenchanted Lowe, as Sam’s contributions to the overall drama

grew thinner over the ensuing seasons.

Joshua Malina, who arrived as Lowe’s replacement in Season Four,

brought much-needed energy as Toby’s sparring partner. While I

found Malina generally annoying on Sports Night, his whiny

annoying qualities worked rather well on WW insomuch as they

provided a springboard for lovely rants by Schiff (it’s also

notable that Malina’s Will Bailey is exponentially less annoying

than Kristin Chenoweth’s altogether useless Season Six addition

Annabeth Schott or the fingernails-on-chalkboard unpleasant

Jeannane Garoffalo—what an amazingly bad call these people

were). After Sorkin’s Season Four exit, the producers moved

Malina into Vice President “Bingo Bob” Russell’s office,

creating even more tension between Malina’s Will Bailey and

Schiff’s Toby, who likely fully expected Will to evolve into the

little brother role vacated by Lowe’s Sam Seaborn. Toby received

Bailey’s defection as an abject betrayal of the president, as

Veep Russell was certainly not the kind of man who should become

president, but Bailey was certainly good enough to make it

happen, getting the goofball Veep elected.

Since I’d missed most of seasons 1-5 on broadcast, I arrived on

the West Wing somewhere in mid Season Six, where some horrible

thing had happened to the show. I was, of course, confused by

the plotlines, but it was only after watching some of the DVD’s

that I realized the broadcast edition of the WW was a vastly

different creature from the show I was becoming acquainted with.

Malina’s Bailey, in Season Six, is a pill. A tiresome,

humorless, ruthless pawn of Veep Russell—himself a humorless,

power-hungry stooge with a flat personality. Which was nothing

at all like Gary Cole’s disarmingly wily vice president, who

came aboard as a schmuck forced on Bartlet by the GOP, and who

used his dull simpleton's image to his advantage, raiding Bartlet’s staff and launching intrigues behind the president’s

back. This was a character with a great deal of promise who, by

Season Six, had been relegated to, basically, one note as he

vied with Democratic rivals for the presidential nomination.

Bingo Bob was many things in Season Five, but he was neither

unlikable nor unwatchable, which he surely was in Season Six.

Same with Malina’s Bailey, a perfectly delightful cast addition,

who, like most of the WW cast, became just another voice in the

mad dash across Season Six.

The heartbeat of the show was, of course, Aaron Sorkin, who

wrote most of the Season 1-4 episodes himself before either

quitting or being fired at the end of Season Four. Sorkin's

legendary dialogue, keen wit, and picture-perfect pacing made

this show, like all of his previous shows, an utter marvel for

me, a writer, to watch. A show that didn’t insult my

intelligence, that taught me things, that made me think, that

made me grow as a writer and as a person. I can forgive all of

the Sorkin ass-kissing going on in the commentaries (it really

gets piled high on occasion), and I suppose I can forgive

Sorkin’s ego being out of whack. He’s really just

that good.

Despite the gloom and doom I heard about Season Five, I found

Season Five to be at least as good as Season Four—which I found

uneven and at times plodding. Schiff steals the show yet again

in Season Five’s “Slow News Day,” where he attempts to save

Social Security and ends up resigning. The late John Spencer,

the brilliant and beautiful man who played White House Chief of

Staff Leo McGarry, more or less owns “Slow News Day,” even

though he’s only in it for two key scenes. The episode, focused

almost totally on Toby, is actually about Leo. About why he’s so

important and about why the president needs to trust him. The heartbeat of the show was, of course, Aaron Sorkin, who

wrote most of the Season 1-4 episodes himself before either

quitting or being fired at the end of Season Four. Sorkin's

legendary dialogue, keen wit, and picture-perfect pacing made

this show, like all of his previous shows, an utter marvel for

me, a writer, to watch. A show that didn’t insult my

intelligence, that taught me things, that made me think, that

made me grow as a writer and as a person. I can forgive all of

the Sorkin ass-kissing going on in the commentaries (it really

gets piled high on occasion), and I suppose I can forgive

Sorkin’s ego being out of whack. He’s really just

that good.

Despite the gloom and doom I heard about Season Five, I found

Season Five to be at least as good as Season Four—which I found

uneven and at times plodding. Schiff steals the show yet again

in Season Five’s “Slow News Day,” where he attempts to save

Social Security and ends up resigning. The late John Spencer,

the brilliant and beautiful man who played White House Chief of

Staff Leo McGarry, more or less owns “Slow News Day,” even

though he’s only in it for two key scenes. The episode, focused

almost totally on Toby, is actually about Leo. About why he’s so

important and about why the president needs to trust him.

Spencer

was, indeed the soul of the show. Spencer

was, indeed the soul of the show.

The much maligned

Season Five should be subtitled Leo Full Throttle, as,

end-to-end it’s the McGarry Show, leading to the concluding

season episodes which clearly foreshadow the heart attack Leo

suffers in Season Six (sadly, the brilliant Spencer died of an

actual heart attack last week). Season Five is a tour de force

of Leo, Leo, Leo, commanding the troops, battling the president

when necessary, thundering through the halls, bitch slapping

Josh after Josh’s ego and arrogance costs the president his

agenda (Josh later brilliantly redeems himself by strategizing

the president through a government shutdown).

Season Five is marred by a certain flailing about in the early

episodes. I enjoyed John Goodman’s President Walken immensely

(“My only regret is we could only kill the bastard once,” a line

no president would ever say, Goodman being an almost perfect

fantasy president and better at it than Sheen), but the writers

didn’t seem to know where to go with the plot. They simply

bing!

found Zoey and that was that. Then they bumped off John Amos’

marvelous Admiral Fitzwallace for, I suppose, emotional punch

for their extremely lame season ender. Fitz was such a beloved

character, and his murder so ultimately useless and meaningless,

that it felt capricious. The character had already retired (from

the Navy and the show, as Amos had taken a role in a (gasps

audibly) WB pilot). If any character deserved a happy ending, it

was Amos. But, instead, they dragged him back to the WW set for

the sole purpose of being murdered by terrorists in order to add

cheap

“emotional punch” to the season finale. A finale that really

didn’t work because it took us too far away from the White House

walk-and-talk which, really, is what the show is about—people

walking through hallways.

Amanda Deavere-Smith’s wonderfully tough-gal Condoleeza Rice

clone Nancy McNally oddly vanished in Season Five after

delivering the wholly unpleasant Mary McCormack as the robotic

deputy National Security Advisor Commander Kate Harper. Harper,

who continues on the show at this writing, was, likely, intended

to be humorously humorless, but now she’s devolved into

Styrofoam. She is thoroughly unwatchable. Smith looked sick and

sounded odd during McNally’s final appearance, as if the actress

had been stricken with some ailment. Her appearance was so brief

as to suggest she was unable to continue on the show.

Season Four was, for me, the weakest season, with Season Two, I

think, being the series high point. Season Three, One and Five

are my likely favorites, with the non-Sorkin Season Five beating

out Sorkin’s final Season Four. I’m reading reviews online

praising Season Six as a return to greatness for the show. It’s

possible I need to see Season Six from the beginning to fully

appreciate it. What I’ve seen so far I’ve not liked. The show

has lost it’s charm and nearly all of its screwball humor. The

West Wing was always on the verge of becoming a comedy, Sorkin

taking us right up to that brink before launching into some

devastating drama. The Season Six episodes I saw had a few lame

attempts at humor, and those were tacked-on, few and far between, as the

tone of the show shifted towards a rushed re-structuring around

the presidential campaign.

The most interesting thing, to me, about Martin Sheen’s Josiah

“Jed” Bartlet is that the producers allow him to be wrong. On

occasion, to be very wrong. Wanting to wipe out an entire city

in retribution for killing his friend (Season One’s

A

Proportional Response), ridiculing and pantsing Vice President

John Hoynes, played with delightful complexity—many parts hero,

many parts bastard—by the wonderful Tim Matheson. Hoynes was another

character who got the shaft for no real apparent reason and

ended up a clownish villainish spoiler, which seemed completely

out of character to the very noble (yet flawed) man Aaron Sorkin

created. In fact, this is probably what I’m trying to say, here:

the show and characters seemed to flatten quite a bit post-Sorkin,

as writers and producers either failed to understand the

complexity of a guy like Hoynes, a guy who really

could be

president (as opposed to Bartlet who was an unlikely winner but

who should be president; the difference between

could and

should being a certain strength of character), and instead

went for simpler notes on the scale (Hoynes bad, Santos good).

Jed Bartlet was both bad and good. I have absolutely no inside

track on this show at all, but it seems fairly telegraphed (to

me) that Toby’s Season Seven confession (and subsequent firing)

by Bartlet was a crock. That the real leak in the whole

draaaaaggged-pout space shuttle subplot was Bartlet himself, and

Toby threw himself on the tracks for the president. I’m sure of

it. I will be devastated to discover I’m wrong, because if I am,

that means the whole subplot was just ordinary—something the

West Wing has never been. Being ordinary is the greatest sin the

current creative staff could make.

From the pilot episode, where Bartlet defends Josh by rudely

throwing right-wing Christian lobbyists’ “fat assess out of my

house,” it was understood that Bartlet could be allowed to be a

complex Everyman struggling with his own faults, with his

resentment of and love for his father and the limitations of

power. He is the smartest guy in the room but, oddly, not always

the most noble. Dulé Hill’s inexplicably fresh Charlie

Young—also lost in oblivion during Seasons Six and Seven—wins my

vote for the most pure soul in the West Wing; Hill’s eyes

usually tell the story, and his character's odd speech pattern

and mixed bag of common sense and incredible intellect make most

every Charlie scene a real treat for my intellect and reason;

Charlie being the kid I used to be before working at Marvel for

27 years beat all optimism, hope, and nearly all intellect out

of me.

Which is not to say Sheen’s Bartlet is not noble—of course he

is. But it is often nobility delayed if not nobility denied or

at least nobility negotiated by the Republicans, the Klingons of

the series who are

regularly villainized and are cut only the occasional break

(most notably with Goodman’s temporary president, who comes

across like a bastard, but in the end was proved right and made

the exact right calls and acted in the best interest of the

nation, despite Josh’s paranoia about handing the Republicans

the White House). Which is not to say Sheen’s Bartlet is not noble—of course he

is. But it is often nobility delayed if not nobility denied or

at least nobility negotiated by the Republicans, the Klingons of

the series who are

regularly villainized and are cut only the occasional break

(most notably with Goodman’s temporary president, who comes

across like a bastard, but in the end was proved right and made

the exact right calls and acted in the best interest of the

nation, despite Josh’s paranoia about handing the Republicans

the White House).

This had to be a great role if not a defining one for Sheen as,

over the years, his Bartlet has been both hero and villain.

Stubborn and emotionally unavailable, arrogant, changing his

mind a dozen times about what Bible he wants to be sworn in on

(to the point where he has no Bible at all and is forced to be

sworn in on a Bible stolen from a red light district motel). A

blowhard and know it all, Sheen’s Bartlet could be

boring,

boring his own staffers who, giddy at the chance of a one-on-one

with the president almost immediately remember why they hate

having one-on-one’s with the president as, when in a chatty

mood, Bartlet would drown you in, say, the history of grapes. Staffers

like Josh or CJ would end up writhing in the guest chair and begging for

relief. In one episode Josh checks his watch and makes a

sideways crack about some dull topic Bartlet is droning on

about, for which Bartlet punishes Josh by refusing to go to bed

but launching into another full hour of something like the

evolution of the cumquat.

I was delighted by the very brave choice to make the president

the best educated man in the room while not always the smartest.

And, had he been the smartest guy in the room, even that would

not help him as the problems that land on his desk require

solutions that nearly always require some measure of sacrifice.

The question of the day was usually whom do we hurt in order to

achieve this greater good? For a compassionate father like

Bartlet, he needed to be surrounded by ruthless politicos like

Josh, and passionate voices like Toby, common sense types like

CJ, and someone who embodies an almost child-like hope for

better things like Sam. The additional battles between Percy

Fitzwallace (Chairman of the joint Chiefs) and Nancy McNally

(National Security Advisor) — two characters (and actors) who

were usually polarized by different perspectives, yet their

respect and immense affection for one another was subtext

clearly available to us (I often wondered if they weren’t having

a thing on the side)—added to the often confounding font of

wisdom this president was surrounded by and often drowning in.

Cutting through the clutter was the First Lady, hastily cast

just a day or so before shooting her first scene. Stockard

Channing has always been one of those actresses I delighted in

most any time I saw her. Here, on West Wing, she got herself

a piece of the rock. Afraid the character would be this empty

(Armani) dress, Channing dragged her feet about joining the cast

until Sorkin (or somebody) guaranteed her the First Lady’s roles

would be meaningful, even though she really is only a recurring

character (this year Channing has wandered off into a god-awful

sitcom with Henry Winkler. As a career move, I understand her

needing to put Abby Bartlet behind her, but, altogether now,

ewwww).

Channing launched herself into the meaty role of the president’s

most senior advisor, and, I have to imagine, her performance in

turn inspired the writers to increasing levels of possibility

with the character (whose screen time inevitably ate further

still into Robe Lowe’s, even though his name remained first in

the credits). Channing’s Abby was the only character who could

call the president “dumbass” and slam a door on him, the most

powerful man in the world made a mere mortal behind the closed

residence doors (or, most remarkably, their knock-down-drag-out

in the Oval Office in Season One’s The White House Pro-Am, an

utterly delightful explosion between the two that was so

convincing you’d actually believe Sheen and Channing—whom Sheen

had never met until five minutes before shooting their first

scene together—had been married for years.

The joke around the set, of course, was that Bartlet’s other

wife, his mistress, was Leo. John Spencer’s McGarry was

unquestionably the most powerful man in the West Wing. As

powerful if not more powerful than the president himself, Leo

was the conscience of the king, the voice Bartlet trusted above

all, perhaps even more than Abby, whose passion could often

cloud her judgment (Pro-Am, Season Four’s

Red Haven’s On

Fire). Bartlet kisses Leo on the forehead as Bartlet is prepped

for surgery, and the love these two men, these two brothers,

have for one another is supremely palatable. Leo would hurl

himself in front of a bus to protect Bartlet, and Bartlet would

tear up the U.S. Constitution to project Leo. Leo knows this and

so his friendship becomes all the more self sacrificing because

he has to keep Bartlet focused while still being his closest

friend while keeping the friendship from becoming the issue of

the day (Season Three’s brilliant Bartlet For America).

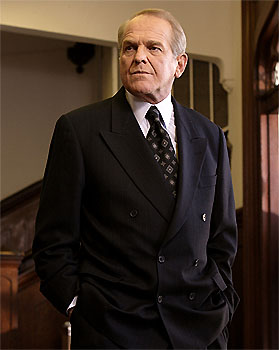

Spencer was absolutely the finest actor in the ensemble. The

only sane man in a West Wing full of nuts. An actor of

incredible range and power, Spencer just chewed his way through

every scene, adopting a quaint, fatherly sideways wobble as he

trundled the labyrinthine West Wing hallways. His face a mask of

authority and purpose, Leo had the ability to NOT get fixated on

what he called, “the knucklehead stuff,” while the president

would often fly off the rails, focusing on minutiae (U.N.

diplomats’ illegal parking in Season Four’s

Swiss Diplomacy,

hanging up on Leo and over-staying his welcome in Season Five’s

brilliant Disaster Relief). Spencer was absolutely the finest actor in the ensemble. The

only sane man in a West Wing full of nuts. An actor of

incredible range and power, Spencer just chewed his way through

every scene, adopting a quaint, fatherly sideways wobble as he

trundled the labyrinthine West Wing hallways. His face a mask of

authority and purpose, Leo had the ability to NOT get fixated on

what he called, “the knucklehead stuff,” while the president

would often fly off the rails, focusing on minutiae (U.N.

diplomats’ illegal parking in Season Four’s

Swiss Diplomacy,

hanging up on Leo and over-staying his welcome in Season Five’s

brilliant Disaster Relief).

I can’t speak for Spencer, but it seemed, to me, that he reveled

in this role, enjoying it thoroughly. I have not seen all of

Season Six, but I am told Leo suffers a heart attack and is

replaced by Allison Janney’s fabulous and popular CJ Cregg—whom

the writers immediately forget how to write for. The quirky

humor, the screwball wit, all gone. Even CJ’s sexiness—she was

attractive in an unexpected way—were lost as CJ was apparently

thrown into the deep end of the pool. By Season Seven (the

current season), nearly all humor and warmth are officially

missing. The writers seem now in such a rush to complete things

before the show’s inevitable 2006 cancellation, all storylines

seem a means to an end, whereas the West Wing was usually about

the journey itself.

Even Sheen’s magnificent creation, Josiah Bartlet, as been lost

somewhere along the way, which is why I’m praying and lighting

candles that I’m right—that Toby’s firing was part of a ploy

orchestrated by Bartlet himself (and that Toby, of course, is in

on it). These two men have had a very special relationship,

Toby being the very last man Bartlet wants to see wander into

his office because Toby is the conscience of the West Wing, the

conscience of the president. His very appearance is painful to

Bartlet, most especially when they’re alone and Toby will,

reluctantly but out of sense of duty, hurl himself into the

whirling knives (asking the president about Bartlet’s father’s

physical abuse in The Two Bartlets, and literally screaming at

Bartlet for hiding his MS from the public in the riveting

17

People).

It is precisely this relationship, this intimacy, this loathing

and love between these two men that lead me to believe only one

of two things are possible: (1) that the current West Wing

creative team is completely lost and have absolutely no clue

what they’re doing, or, hopefully (2) Bartlet himself was the

security leak, and Toby grabbed the third rail when he realized

it was his boss and news of that getting out would have gotten

Bartlet impeached.

With the ratings in major decline, NBC did what most networks

do—they moved the show to the Sunday night graveyard just as

millions of new fans, like myself, were discovering this show

via DVD. It was an incredibly stupid move, one capriciously

designed to hasten the show’s death, but a move common to

network execs who, frankly, have never been the brightest people

on the planet. I’m not entirely sure I disagree with their

choice. The West Wing threatens to devolve into a lame

self-parody. With a very few exceptions, the writing is simply

atrocious, the characters are all treading water, and the magic

of the show (I believe the show was typically written as a

comedy and then pulled ever so slightly back from the brink) is

all but completely lost. All of the actors look stressed, whether

their parts call for it or not.

The producers have invested some real cash in Jimmy Smits who

just can’t find Matthew Santos and whose pulpit oratory is

severely lacking. Given Santos’ wealth of screen time, it seems

obvious they were grooming him for Sheen’s replacement, but

Smits is simply outgunned by the marvelous Alan Alda, the one

beacon of hope on the show these days (though notably missing

from the Season Seven cast image), who takes Smits

clean out

as an actor with an easy smile and a single line (most notable:

Alda’s 18-second appearance at the end of the Season Six finale

where he turns and says, “Okay. Now let’s go win this thing.”

You really won’t understand the power of Alda as an actor, as an

iconic figure, until you see him demolish a tour de force hour

of dizzy hand-held camera angles and super-fast deal making with

a single line of dialogue).

The only hope I have for a Season Eight is an Alda presidential

win. Smits is just not interesting enough and, like Lowe, not

giving the writers enough character to chew on. Moreover, the

actor who portrays Santos’ wife couldn’t possibly be less

interesting. The very idea of six years of Smits stumbling

around trying to find his character, with what appears to be a

terribly miscast cipher on his arm, is not inspiring at all. A

brilliant actor, Smits was once so invested in

L.A. Law’s

Victor Siffuentes, nobody thought he could make a convincing New

York cop. But, five years into NYPD Blue, Siffuentes was all

but forgotten as Smits had become Bobby Simone, who now haunts

his West Wing performance. Smits’ stellar performance as the

dying NYC detective now dogs his efforts to reinvent himself

here, as Matt Santos indeed comes across like a shell or a

shade, a dead man walking.

It is entirely possible, if not likely, that any dire

predictions I make here are short-sighted and wrong. Being found

wrong is one of the few joys left to me in life, when people

smarter and more clever than I can surprise and delight me with

the unexpected. But with the tragic loss of Spencer, with Sheen

apparently eager to move on before his Bartlet is rendered

completely impotent, with the sagging ratings and with no

apparent creative bright spots on the horizon, I am quite sure

we are seeing the last season of this landmark show, a show

which was, ultimately, a personal statement of its creator, and

one which did not fare well without him.

This was a fairly amazing show and rare for television: a show

that not only delighted us but informed and educated us, all the

while plumbing the untapped depths of literature and literacy. A

show that didn’t insult our intelligence but rather challenged

it. Having my writing compared to this was, indeed, a great

compliment, but I’m nowhere near this level. But this is the

league I wanna play in.

Christopher J. Priest

27 December 2005

DISCUSS THIS ESSAY

TOP

OF PAGE

THE WEST WING

images and sound clips Copyright © 2005 Warner Bos Entertainment Inc., A Time Warner Company. All Rights Reserved.

Text Copyright © 2007 Grace Phonogram eMedia. All Rights Reserved.

|