|

What

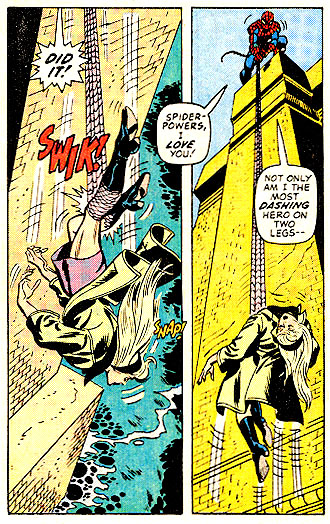

absolutely floored me was not just that Spider-Man

could move, but that he

moved like Spider-Man. Not like Tim Burton's idea of how Batman

moves, but how Spider-Man actually moves. This was a film

obviously created by people who actually knew something

about Spider-Man. People who loved Spider-Man and who cared a

great deal about getting it right. They didn't approach the

material in a patronizing manner, something Hollywood has an

incredibly difficult time with. The first hour or so of Superman

was one of the most brilliant moments in super-hero film, but

then they just wrecked it by immediately camping it up soon as

Clark hit Metropolis. The first couple of reels of Tim Burton's Batman

were darkly gothic and a real pleasure to drink in, but Burton

couldn't help himself when he got to Nicholson's Joker, and the

taut plot careened off a cliff and never recovered.

Spider-Man remained disciplined from opening credits

to the final shots of Spidey doing his thing. It set a new

standard: Make It Good. Don't just make it work, but Make It

Good. If you Make It Good, they will come. They will come in

droves. And, better than that, they will go. They will go and

tell people, and other people will come. Spider-Man broke

$100 million in its opening weekend, a figure I guarantee you

not even Stan Lee (whom I know, so I'm not talking out of my

hat, here) could have possibly dreamed. Spider-Man had

Marvel all over it, with both Lee and Marvel top dog Avi Arad

actively involved, where the tradition as, typically been, to immediately

exclude the comic book guys as soon as the deal is inked. Marvel

is all over this film and it shows. There are dumb things

about Spider-Man— the really bad Goblin mask for one, I

almost didn't see the film because of it, and I almost walked

out when Willem Dafoe first suited up— but the amount of

dumbness was clearly kept to a minimum, and I refuse to accept

the idea that that's a happy coincidence. That's what having

Stan Lee in the room gets you.

So the new standard, Make It Good, includes, as a prime

component, Keep The Comic Book Guys In The Room, Moron. This Is

What They DO For A Living. In case it doesn't show, I am

flat-out overjoyed by Spider-Man, a film that may

actually help keep comics alive, as opposed to, say, the Joel

Schumacher gay fest Batman & Robin. I have no problem

with gay fests per se, but Schumacher was making fun of Batman

and company and paying Ahh-nold (I still can't believe it)

twenty-five mill to do it. Batman & Robin not only

killed the Bat franchise, it nearly killed the notion of

super-hero flicks altogether. I'm not sure when or if we'll ever

see Batman suit up again, but Spider-Man has made Black

Panther that much more likely, as now Snipes has to

be thinking, "Spandex sells." Of course, at this writing,

Snipes' team has violated the new deal. They have kept the comic

book guys out of the room. I hope that changes. A recent article

in one of those film previews magazine had sound bites from

Snipes talking about Panther, but talking about Panther

in a way that shows us he's never read the current incarnation

of the character. In fact, the article published a BLACK PANTHER

comic book cover to go along with the article— issue #7 of the

greatly lamented and very silly Jack Kirby run. I hope Snipes

learns the Spider-Man lessons. If he makes the Kirby

Panther, the Joel Schumacher Panther, I may just have to kill

myself.

I'm not sure where the misfire was on Mary Jane. MJ was a man-eater:

a fiery and outgoing person who immediately became the life of

any party and sucked all the air out of any room she walked

into. MJ was aggressive in a playful way, very direct, and used

to make Peter's knees shake just by looking him in the eye. She

was not this... onion... Dunst portrays in the movie, who has no

idea the boy next door has a crush on her. Stan Lee's MJ knew everybody

had a crush on her. She didn't use it to an unfair advantage,

but she had fun with it. She was a party girl. She called Peter,

"Tiger," which was her way of gently mocking him

(actually, she called all the guys, "Tiger," because

there were too many guys to remember all the names). Mary Jane

was a much brighter personality, a much sharper person, than the

Dunst character, who came across as a little vapid and very

bland. Dunst was playing more of Gwen Stacey, Peter Parker's

actual love interest (his romance with MJ didn't really kick

into high gear until Marvel decided to pervert my Spider-Man

versus Wolverine into an excuse for the two to get married,

but that's another story).

I think the film wimped out by not killing Dunst's character.

In the comics, the Green Goblin tosses Gwen Stacey off of the

Queensboro Bridge. Spider-Man saves her with his web line, but

the shock of the fall, and the whiplash of the sudden stop,

snaps Gwen's neck and kills her. This was one of the most

brutally shocking moments in the history of comics, one that

hundreds of writers, including myself, have attempted to top. It

was one of those seminal, almost religious moments where the

standard has been set. Gerry Conway's brilliant writing of The

Death of Gwen Stacey stands as a landmark in comics history, a

moment so shocking it just left twisting for a month, refusing

to believe she was dead, thinking Spidey would get Dr. Strange

or somebody to resurrect her. But, no, she was gone, and that

death and the subsequent showdown with Norman Osborne's Green

Goblin constitute likely the best 44 pages of comics ever

written or drawn (art by the fabulous Gil Kane, tempered by the more

familial inks of legendary Spider-Man artist John Romita).

Has Willem Dafoe tossed Dunst over the bridge, and Maguire saves her only to realize he has not, in fact, saved

her— my

lord, that would be some movie. I have no doubt this scenario

was played out as some point in the development process, but

scratched likely under pressure of the looming franchise and

merchandising. This creative choice was likely one not even Stan

or Arad could change, although every Spider-Man fan knows

what actually happened on that bridge, and every

Spider-Man fan likely walked out of the film knowing they

chumped out when the going got rough: when the film actually

came close, for a brief moment, to the actual intensity of real

comics.

|