|

OFFICIAL WEBSITE OF CHRISTOPHER J. PRIEST | the death of the black panther There was a rumor going around that, shortly before the launch of BLACK PANTHER, Chris Claremont— Marvel's Director of Quality Control at the time— scoffed that the book wouldn't last six issues. The rumor had it that Marvel Knights honcho and PANTHER Editor Joe Quesada, angered and annoyed that a Marvel officer was prejudicing people against his book, stormed into Claremont's office, put a thousand dollars in cash on Claremont's desk, and demanded Claremont either shut up or put his money where his mouth was. I am told Claremont did not take Joe's bet. As it turns out, that was a good thing (and, rumors being rumors, I'm sure this big fish story has been embellished over time). At this writing, I am spending the weekend re-writing scenes in BLACK PANTHER #53, the fifty-third issue of a book nobody (myself included) thought would go past issue #12, but a book that has been dogged, from issue #1, with rumors and predictions of cancellation. Cancellation has always been in our lexicon, has always been a part of the creative process. So much so that the looming possibility no longer holds much terror for us. In fact, I am royally sick of talking about it, of answering questions about, "When do you think the book will be cancelled?" and, "Are you worried about the book being cancelled?" No, I am not worried. I've never been worried. I'm a writer. Every month I turn in a story, until somebody calls me and tells me to stop. At which time, I guess, I'll go onto something else. That's the nature of the business: your book gets cancelled. Or you get tired of working on it. Or you get fired. It's hard to take any of it personally: you just do what you do. The Death Watch on PANTHER is annoying, to be sure, and not knowing when the ax will fall does make long-term plotting difficult. But, beyond that, the issue of whether The Black Panther lives or dies is something larger than our ability to do much about.

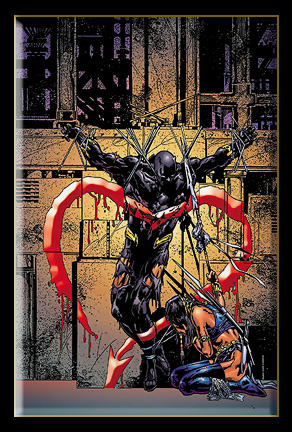

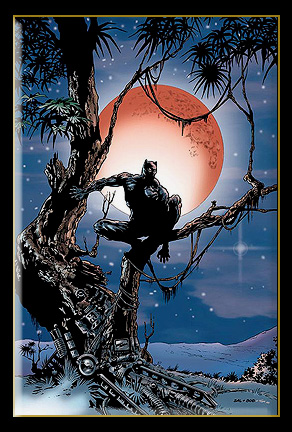

Art by Sal Velluto and Bob Almond. © 2003 Marvel Characters, Inc.

BLACK PANTHER has never been a huge seller. I have doubts that it ever WILL be a huge seller, and I have articulated my reasons why here. The ideal of diversity within traditional super-hero comics is often at odds with the demographic of the consumer base, which is largely composed of long-time fans who have forged relationships with favorite characters over the years. I'm sure Black Panther was somebody's favorite character as they grew up, but the hero's legacy is one of an also-ran whose Big Talk African aristocracy rather prohibits much in the way of snappy dialogue. Readers want to identify with their heroic fantasy, and a great many fans want to read about fantastic adventures set in what Stan Lee once called, "The World Outside Our Window." Wakanda, a technologically advanced African nation steeped in tribal tradition, hardly qualifies, and, the race of the character notwithstanding, the cool aloofness and formal Big Talk successive writers created for him inspired less curiosity as disinterest. As often as not, The Black Panther came off more boring than mysterious. It seemed to me, as a reader, the writers simply didn't know what to do with this man who had no super-powers, no snappy dialog, no berserker rage and no obvious character faults to capitalize on. Over the years, Panther became a sideshow. Stripped of his advanced tech, that Reed Richards marveled at in Panther's first appearance in FANTASTIC FOUR #52, a mindset evolved that Panther, for some odd reason, created incredible advanced technology while eschewing the use of the same. I believe someone explained it to me that Panther feels a true warrior doesn't need bullet-proof costumes or global positioning communicards. That, to prove himself a man and a true warrior, Panther would go into battle side by side with the likes of Thor and Iron Man, and not take so much as a flashlight. What was even odder, for me, was the uproar of fans outraged by our evolution of the character into an extremely capable and not always clearly heroic figure, a man of uncertainty and mystery who used all of the vast resources at his disposal to accomplish his goals. Cries of heresy went forth from readers who hadn't ever read our book and, more to the point, who likely didn't support BLACK PANTHER in any of the several incarnations of ongoing adventures Marvel has attempted. Expletive-laden rants came in from people who know nothing about Panther, never really bought Panther on any regular basis, and who, frankly, think Panther is lame but who have bought into the severely errant illogic of the day— the de-evolution of a very clever and very unique character created by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. Again and again I was asked, "How dare you change Panther!", to which I replied, "I didn't change Panther— other writers over the years changed Panther, losing sight of FF #52. *I* changed him back."

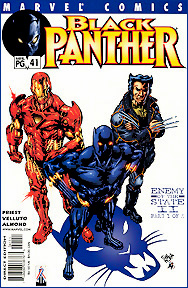

Color concept for BLACK PANTHER #32. Copyright © 2003 Marvel Characters. All Rights Reserved.

But, even so, I knew the character would be a long, hard sell. Minority characters and female characters have traditionally made a poor showing in the marketplace, a simple reality of supply and demand. And, demand for BLACK PANTHER has never been much of an incentive for keeping him around. I was so convinced, in fact, that PANTHER would be cancelled with issue #12 that I never wrote issue #13. I received a phone call from an anxious Ruben Diaz haranguing me about the next plot. "The next plot to what?" I asked, in all sincerity. News that BLACK PANTHER, newly dropped from the Marvel Knights pantheon, would actually reach issue #13, seemed nothing short of a minor miracle to me. Now out of the safety of Joe and Jimmy's boutique, PANTHER had to fend for itself in Bob Harras' shop, where Chris Claremont— Newman to my Jerry— wandered the halls unescorted, scribbling his little witticisms in the margins of scripts he read as Marvel's quality control czar. I couldn't fathom why we were allowed to live. I knew Bob Harras, but I was not pals with Harras the way I was pals with Joe and Jimmy. Bob was, um, Ann Nocenti's assistant. A nice enough guy, but that's about all I remember of him before his career skyrocketed with the X-MEN craze and ultimately landed him in Tom DeFalco's big chair at Marvel. Much as I'd like to oblige the rumor mills with more anti-Bob blather, Harras always returned my calls. He was polite and fair, actually helping me battle the dreaded Claremont on more than one occasion. In fact, Claremont himself was reported to not only enjoy reading PANTHER, but wanted to borrow Everett K. Ross, Panther's U.S. State Department handler, for an arc in FANTASTIC FOUR. When we wanted to borrow Storm for an issue of PANTHER, to build on work Claremont began in MARVEL TEAM-UP #100, Claremont not only didn't balk at the idea, but went out of his way to write Ross into an issue of X-MEN to set up the encounter. So, suddenly, I saw no enemies where enemies should have existed. There were only people interested in keeping the book on the stands. A book nobody thought would last six issues.

Although our sales indicators keep us in the red zone, by nearly every other indicator we are at the top of our game. Having jettisoned a lot of continuity baggage with the Return of the Dragon arc, PANTHER was able to start relatively fresh with Enemy of The State II in BLACK PANTHER #41. Writing the issue for what we'd hoped would be a group of first-time readers who would know nothing about the book or the cast, we leisurely introduced the main and supporting characters in the first chapter of the new arc before splintering the story off into three separate and seemingly unconnected storylines. Readers coming in on the middle of Enemy II will likely find themselves trying to decipher a Chinese menu of subplots and art styles. But those willing to hunt down the previous issues for the entire hit of Enemy II should find it easy to follow and the most straightforward arc we've done in quite some time. But, we're still in trouble, and, as the story goes, the bean counters at Marvel came to Marvel EIC Joe Quesada and wanted PANTHER cancelled. Kaput. Fini. Th-th-that's all, folks! At the height of our work together, we were shot down. But, then, two odd things happened: (1) Quesada gave PANTHER a reprieve by raising our cover price an extra quarter, pushing PANTHER's price up to $2.75 per copy, or 50¢ higher than Marvel's standard line price. And, (2) Peter David picked a fight with him because of it.

David, a top flight writer and fan favorite (and also a close friend of mine) was the writer of a book which, like PANTHER, was struggling for survival: CAPTAIN MARVEL. MARVEL, along with PANTHER and Tom DeFalco's SPIDER-GIRL, were three low-selling but highly prized cult favorites slated for cancellation before Quesada and Marvel Publisher Bill Jemas devised the new pricing scheme. The logic was, since efforts to widen the audience for these titles have thus far failed, the only alternative to losing the books outright would be to ask the core audience to dig deeper to support them. This is the same concept that pushed STEEL's cover price to fifty cents over DC's standard pricing, which caused sales to immediately plummet. The difference here, though, was, while PANTHER is arguably at its creative peak, STEEL was, by that time, a shell of its former self, produced by a disheartened and demoralized creative team. PANTHER was invigorated, while STEEL had the stench of death about it. I never worried about the price increase. I really do believe in this book, in the integrity of our work, the commitment of my creative partners and the co-commitment of the fans who rabidly support us. I never doubted our core audience would shell out the extra quarter to keep us around, and most would do it cheerfully and thankful to Joe and Bill Jemas for finding some formula to buy us a stay of execution. When I was told about the price increase and the reasons for it, I eMailed Joe a thank-you note for his efforts at keeping us in business. Peter David's Open Letter to Joe Quesada and Bill Jemas was posted on Newsarama, a comics trade web site, in mid-March. Suddenly, everyone and their mother was writing me, asking me what my opinion of the price increase on CM, BP and SG was, and what I thought of Peter's challenge to Joe— to write his book, essentially, for free if Joe would agree to keep the cover price down. Message boards and other trade sites came alive with the bickering between Joe and Peter. Suddenly, all three books were thrust forward into the limelight, enjoying, perhaps, the biggest publicity push any of us have ever had, while grouping the fate of all three to whatever policy emerged from this very public spitting contest. Which, cynically, beggars the question: was this just a publicity stunt? I don't know. I can only speak to my role in it, writing what I thought was an amusing rebuttal in An Open Letter To Peter David, playing devil's advocate, sticking up for Joe (against unrealistic and unfair inferences in Peter's letter), and kind of asking everyone to join hands and sing. My letter did not amuse Peter, and frank discussions ensued between us that are personal and will remain so. However, I doubt Peter's deal was a publicity stunt any more than my genuine concern was. A Cincinnati retailer whom I do not know and have done nothing whatsoever to, viciously attacked me on Newsarama's message boards, calling me, "Quesada's bitch." It was all quite exciting.

And, just as fast as it arrived, the hubbub departed, taking our publicity blitz with it. Joe unilaterally retracted the notice of price increase, holding all three books— BP, CM and SG at their current cover prices for the immediate future (but with no guarantees). While I suppose this signals some manner of victory on Peter's end, I pray it does not become a Pyrrhic one. There was some small component of security implicit in the price increase: the public statement from Quesada and Jemas suggested these titles would be given a six-month reprieve at the higher price point before being evaluated for cancellation again. By holding the line at the current price, there is no suggestion of a guaranteed run. I'm not sure that taking the fifty cents and six months wasn't the better deal, and I'm really afraid of BLACK PANTHER's fate being decided by the David-Quesada/Jemas Byzantine pajama party. But, on the other hand, as far as I'm concerned— by keeping us on the stands 47 issues longer than anybody predicted— Marvel Comics has certainly earned the right to be heard on The Panther's future. I've been given a relatively free hand to craft the series as I see it, with almost no interference from Marvel. Would we like more promotion? Certainly. But, I honestly have no regrets about our run on BLACK PANTHER. If Marvel decided to, tomorrow, turn Panther into a book about burly construction workers who like to wear ballet tutus in their off-hours, I'd consider it. They've given me nearly 50 months to try things my way. If and when the shoe ever does drop, I'll have no regrets about this experience. I'm actually glad Joe and Jimmy talked me into it.

The greater threat to BLACK PANTHER, at the moment, is not Bill Jemas, Joe Quesada or even Peter David. It is not Klaw, Killmonger or Man-Ape. It is the inoperable brain aneurysm caused by Panther's battle with Iron Fist during our Return of The Dragon arc. The irony of Dragon..., an arc designed to eliminate a bunch of continuity baggage that had been dragging the series down, being the catalyst for Panther's demise (and using Iron Fist, who was himself once killed by a random and meaningless act) is deliciously apropos. The major complaint about Panther the character and PANTHER the series in our Marvel Knights revival has been that the Black Panther seems too invulnerable, too all-knowing, too far ahead of the game to ever lose. The complaint has been: he's a guy who never loses. Which is highly inaccurate. Besides the several good whuppings Panther has endured on my watch, he has lost a great deal. He lost his own future by abandoning his fiancé, Monica Lynne, for reasons to be finally revealed in issue #49. He's lost the camaraderie of The Avengers by revealing to them he'd only joined the group, initially, to satisfy himself that they were no threat to his native Wakanda. He's lost the soul of an innocent child, Nakia, his charge, whom he trained from puberty to be a lethal assassin. A girl who went nuts right under his nose, and he hardly noticed until Nakia tossed Monica Lynne out of a moving plane in a fit of jealous rage (issue #12). Nakia became the deadly Malice, using the training Panther gave a too-young and too-start-struck child to murder innocent protesters outside of the Wakandan Consulate. He's lost stature and the admiration of the American public by nearly crashing the world economy just to one-up Killmonger (issue #18-20) and by nearly starting World War III by blockading Deviant Lemuria and drawing Prince Namor, the Sub-Mariner into the conflict ("Sturm Und Drang," issues #26-30). Panther has had to threaten two tribes within his own kingdom— The Q'Noma (issue #33) and the Jabari (the Cult of the white Gorilla, in issue #35)— with death, thus fomenting division and tribal unrest that led to several tribal clashes which cost hundreds of lives. On my watch, we've seen, time and again, that Panther is wholly vulnerable and subject to human failure. He's ultimately won, and always done the noble thing, but, each victory has cost him dearly and almost always in blood. King T'Challa of Wakanda, as a result of this series run, is one of the loneliest and most isolated figures in the Marvel universe. This is a discipline he chose for himself, a sharp personality shift that took place suddenly, between Don McGregor's lavish Panther's Prey and issue one of this current series. The consequences of that discipline, of the tough choices he's had to make, forms the basis for this summer's THE DEATH OF THE BLACK PANTHER.

THE DEATH OF THE BLACK PANTHER, which begins this summer in BLACK PANTHER #48, signals a major evolution in the creative focus and direction of this series. A brooding and semi-delusional King T'Challa has barricaded himself in his newly-rebuilt throne room. Everett K. Ross has been camped outside the king's door for the three days the Panther has remained inside, alone, without food or water, suffering some kind of emotional breakdown. The Panther is haunted by his failures. By the steep cost of his commitment to his father's legacy and to the people of Wakanda. He's given up too much. He's drawn himself in so far, it is now impossible for him to reach out. He is dying. Surrounded by friends, yet completely and utterly alone. Damned to a hell of his own creation as the all-too-real ramifications of his lifestyle and personal sacrifice exact a terrible toll. And, the worst of it: he realizes he is becoming exactly what Storm (from the X-MEN) warned him he might: The Black Panther is becoming a villain. Back in issue #27, Storm warned Panther, if he didn't change, he was in danger of going the same route Magneto went. He was in danger of becoming just like Magneto. With time running out for him, and much to accomplish in his kingdom and abroad, Panther suddenly finds his ends increasingly justifying his means to the point where Storm's words fairly haunt him as he realizes he has descended to the very end of an increasingly shorter rope: that, not only is he physically dying, now he is dying spiritually as well. He has become his own worst enemy: a tortured man who is destroying himself. Like Donald Blake's cane, Panther's aneurysm is intended to be what St. Paul called, "a thorn in my flesh": a damningly human vulnerability that grounds T'Challa somewhat and keeps him keenly aware of his own limitations and the consequences of his constant scheming. His illness, as permanent (and terminal) as is this writer's tenure with the character, is a wholly self-inflicted one: borne out of T'Challa's arrogant challenge to the powerful mystic dragon Chiantang in the story arc Return of The Dragon. Chiantang, having been one-upped by Panther, chose Chiantang's most hated enemy, Iron Fist, as his champion. He brainwashed Iron Fist and sent him off on a murderous campaign to destroy Panther. Panther was able to subdue Iron Fist, but not before succumbing to Iron Fist's superior martial arts skills and falling prey to repeated hammering by the deadly power of the Iron Fist. Now facing an uncertain future and consumed by grief and loss, Panther finds his multi-layered planning to be of no use to him. His friends and loved ones, whom he's kept guessing and at arm's length, find themselves completely unable to know whether his melancholy is real or merely another component of his latest scheme. All anyone can do is wait to see what ninth-hour reveal proves Panther to still be the master of political manipulation— — or, whether they'll have to eventually break down the throne room door, and what they'll find inside if they do.

It is likely we could continue to exist in our current vein for years to come, but likely always with the cloud of cancellation hanging over our heads. Or, we could make a bold move into the next level of adventure and intrigue. With a PANTHER film on the verge of going into production, and T'Challa's renewing his active member status with the AVENGERS this summer, it is a fair guess the title THE DEATH OF THE BLACK PANTHER is likely more rhetorical than literal. I am, after all, hard at work on the story arc after Death..., so, obviously, Panther will still be here. But, and you've heard this before, things will never again be the same. They can't be. It is, simply, time to move forward. And time to reconcile this book's ambitions with the reality of the marketplace in which it competes. THE DEATH OF THE BLACK PANTHER thematically represents the tough call to make the tough call. With no guarantee that current PANTHER fans will like the new direction this book will take with issue #50, and absolutely no guarantee that the new direction will attract sufficient new readers to make any real difference in the numbers. The rock and hard place T'Challa finds himself between resonates with the one we've all (fans, creators, and company) struggled with for four years. And, while we're all quite excited about the evolution that begins with our 50th issue, the decision to move forward inevitably means leaving some things behind. We are all quite sad about those things lost, the death in the family. A death that will make for, we hope, one of the most powerful statements of this series to date. THE DEATH OF THE BLACK

PANTHER begins in issue #48.

Christopher Priest

Please do not link to

images or music here for your site. This site is for promotional purposes only, and in no way challenges the exclusive copyright ownership of the sample materials represented here. All Marvel Comics content Copyright © 2003 Marvel Characters. All Rights Reserved. All DC Comics content Copyright © 2003 DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. All other stories, art, photos and other intellectual properties as may be represented here are copyright © and are trademarks and/or registered trademarks ™ of their respective copyright and trademark owners. All rights reserved. |

Three years later, we're still

here.

Three years later, we're still

here.

THE DEATH OF THE BLACK

PANTHER is both an ending and a new beginning, as the BLACK

PANTHER series, awash in critical raves, must nonetheless respond to the imperatives of the marketplace it

has

never truly flourished in. At the end of the day, nobody at

Marvel forced us to make creative changes with PANTHER. I

haven't had even one conversation with Joe Quesada about this,

even being his bitch and all, and the notion that Marvel wants

to cancel this book is patently absurd. It is just that the

formula for expanding our reader base to a healthy level has, to

date, escaped us.

THE DEATH OF THE BLACK

PANTHER is both an ending and a new beginning, as the BLACK

PANTHER series, awash in critical raves, must nonetheless respond to the imperatives of the marketplace it

has

never truly flourished in. At the end of the day, nobody at

Marvel forced us to make creative changes with PANTHER. I

haven't had even one conversation with Joe Quesada about this,

even being his bitch and all, and the notion that Marvel wants

to cancel this book is patently absurd. It is just that the

formula for expanding our reader base to a healthy level has, to

date, escaped us. Postscript:

Postscript: Guest artist Jorge Lucas brings both an immense sense of humor and an immense respect for the work of the late John

Buscema. I worked with John for years as his editor and later his writer on CONAN THE BARBARIAN, out of Larry Hama's office at Marvel. THOR Editor Ralf (The Waste) Macchio teamed Buscema with P. Craig Russell to create a gorgeous classic Old West for THOR #370, a fill-in story I'd written. The story was a lot of fun, with card sharks and bandits and train robberies and, in the midst of it all, Norse Gods fighting a war on our turf. If you can find

a copy of THOR #370, I encourage you to snap one up. Jorge has painstakingly recreated whole scenes from that story in

Saddles Ablaze, which lands our PANTHER cast smack between the pages of a comic story I wrote 16 years ago. You don't need THOR #370 to (hopefully) have a belly laugh or two at our Mel Brooks-ish farce, but having it will definitely lend dimension to

Saddles..., which we have dedicated to John's memory.

Guest artist Jorge Lucas brings both an immense sense of humor and an immense respect for the work of the late John

Buscema. I worked with John for years as his editor and later his writer on CONAN THE BARBARIAN, out of Larry Hama's office at Marvel. THOR Editor Ralf (The Waste) Macchio teamed Buscema with P. Craig Russell to create a gorgeous classic Old West for THOR #370, a fill-in story I'd written. The story was a lot of fun, with card sharks and bandits and train robberies and, in the midst of it all, Norse Gods fighting a war on our turf. If you can find

a copy of THOR #370, I encourage you to snap one up. Jorge has painstakingly recreated whole scenes from that story in

Saddles Ablaze, which lands our PANTHER cast smack between the pages of a comic story I wrote 16 years ago. You don't need THOR #370 to (hopefully) have a belly laugh or two at our Mel Brooks-ish farce, but having it will definitely lend dimension to

Saddles..., which we have dedicated to John's memory.