The achievement of the film is not that it answers the mystery of the Kennedy assassination, because it does not, or even that it vindicates Garrison, who is seen here as a man often whistling in the dark. Its achievement is that it tries to marshal the anger which ever since 1963 has been gnawing away on some dark shelf of the national psyche.

óRigger Ebert, Chicago Sun-Times

Quoting everyone from Shakespeare to Hitler to bolster their

arguments, Stone and Sklar present a gripping alternative to the

Warren Commission's conclusion. A marvelously paranoid thriller

featuring a closetful of spies, moles, pro-commies and Cuban

freedom-fighters, the whole thing might have been thought up by

Robert Ludlum.

óRita Kempley, Washington Post

There Are Four Lights

The climax of

Chain of

Command, arguably one of the best episodes of Star Trek:

The Next Generation, features a starving and dehydrated

Captain Jean-Luc Picard ranting at his Cardassian tormentor,

played to disquieting perfection by the wonderful David Warner.

ďThere... are... FOUR... LIGHTS!!Ē Picard shrieks, the otherwise

polished legendary Shakespearean actor Patrick Stewart losing

all dignity and composure as his Captain Picard shrugs off

assistance from Cardassian guards and stumbles out of the

torture chamber. The point of the exercise had been for Gul

Madred to break Picardís will through various renditions

techniques until Picard would begin to deny what his eyes

plainly see--the four lights above Madredís desk. Madred

repeatedly insisted there were five lights. Torture victims,

desperate to end their suffering, would agree to say whatever _

wanted to hear, but that was not enough. Madred insisted his

victims not only say there were five lights, but believe it to

be true.

Convincing people to ignore what their lying eyes tell them is a

time-honored tradition likely as old as mankind itself. Frame

312 of Abraham Zapruderís crude 8 mm film shows the head of U.S.

President John Fitzgerald Kennedy move slightly forward, which

has been used to argue that the fatal head shot was fired from

above and behind the president. But frame 312 is also where

Secret Service Agent William Greer hit the brakes, bringing the

presidentís car to nearly a complete stop, likely reacting to

the sound of gunfire and, per many conspiracists, a bullet

hitting the windshield above the rear-view mirror.

When Robert Groden, author of The Killing of a President, asked for an

explanation, the FBI responded that what Groden thought was a

bullet hole ďoccurred prior to Dallas.Ē A researcher

later found a Ford Motor employee who had helped build a new

windshield for the car, who said he and his co-workers had been

told to destroy the old windshield, which had a bullet hole from

the front. [Wikipedia]

Frame 313 unquestionably portrays the president being struck in

the face by a shot fired from a high-velocity rifle (as opposed

to the medium-velocity Oswald weapon) unquestionably fired from

the front and right of the presidentís motorcade. Eyes are

undoubtedly rolling even as my words are being read, but itís

true. If that image, frozen in time, were of any other person,

during any other incident or attack, a first glance at the image

of a man being struck on the right side of his face, his body

jerking backward, his head snapping to his left, the

interpretation of that image would, 10 out of 10 times, be that

this person was shot from the front.

As much fun as we like to have with Oliver Stone, in the history

of gunshot wounds, it is only and singly this image of U.S.

President John F. Kennedy that we insist depicts a man being

shot from behind and from a high angle, even when the back of

the presidentís head explodes and skull pieces fly out toward

the rear at a straight, flat trajectory. It is the people who

stubbornly refuse to agree this image depicts a rear, high shot

who are branded nuts. There are five lights.

In 1979, the House Select Committee on Assassinations concluded

there were four shots, one coming from the direction of the

grassy knoll.

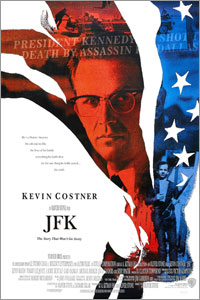

Not Guilty: New Orleans Distrct Attorney Jim Garrison (Costner)'s riveting

(and largely fictionalized) closing argument.

An Alarming Lack Of Objectivity

During this 50th commemoration of the presidentís assassination

it deeply disturbed me to have seen, repeatedly, in mainstream

and cable news, a dismissive hand-wave to conspiracy theories.

Oswald Did It, was the refrain across competing news sources and

networks. Conspiracy Buffs Wear Tin Foil Hats. And, you know,

maybe they do. What disturbed me, however, is it is certainly

not a journalistís duty to tell me what to believe. A

journalistís duty is to report facts and treat me like an adult

capable of reaching my own conclusions. But headline after

headline, over the course of this anniversary, reinforced the

Oswald legend, telling gullible Americans what to think--a job

best lefty to the tabloids.e critical X-Rays and other evidence and

documents related to the assassination is the governmentís

refusal to say, in even oblique terms, why. JFK conspiracy

theories are, in fact, fueled by our own government, by the lack

of why. ďNational Security,Ē isnít a reason. If there were even

the slimmest hint of why these documents are still, 50 years

later, not being made public, Iíd happily pack up my cynicism

and be on my way.

Instead, we get more stonewalling, which only keeps the

conspiracy bandwagon rolling. The chief argument against

conspiracy is the oft-repeated question, ďHow do you manage to

keep so big a secret among so many individuals for so long?Ē The

consistent answer to that question, thanks to the governmentís

stonewalling, is obvious: ďNational Security.Ē You convince

people the nation would be harmed if the truth came out, which

may well have been true in 1963 but is hardly true now. If the

government revealed, for instance, that Castro was behind it

all, does anybody seriously believe the U.S. would now invade

Cuba? And, if the U.S. invaded Cuba now, does anyone seriously

still believe Russia would start World War III over it?

The whole notion is entirely foolish. But, in the 1960ís,

getting people to shut up on the grounds of national security

was a fairly simple thing to orchestrate. ďWe canít let the

truth come out because, if it does, thereíll be a nuclear war.Ē

So they label the e tracheotomy site on the presidentís neck as

an exit wound, pull a swapitty-doo with the body on its way to

Bethesda so the missing scalp and hair have largely been

replaced and the massive exit wound on the back of the

presidentís head now appears to be a rather intact wound of

entry. And so on. And everybody destroys their notes and keeps

their mouths shut. Why? Because they are not cops or reporters,

they are military men and women under orders and the fate of the

nation, if not the world, is at stake.

Or not. But, so long as the government refuses to release those

documents, such refusal suggesting there is contained therein

information harmful to the national interest even at this

advanced age, even this far removed from the old Cold War. Mock

and scoff all you want, but none of the detractors, including,

bizarrely, so many news outlets standing shoulder-to-shoulder

not reporting facts but literally telling us how to think, can

answer a simple question: not whatís in those secret papers by

why, at this late date, are they still being withheld.

You could shut these people up with a stroke of a pen: simply

release the documents, and weíll see just how crazy Oliver Stone

actually is.

An

American Masterpiece

An

American Masterpiece

Iíve no interest in debating JFK conspiracy theories. If you

want to believe in Oswald and the book depository, be my guest.

But donít try and sell me on frame 313 being anything other than

what it clearly and obviously is: a shot from the front on a

low, flat trajectory consistent with ďBadge Man,Ē the

unidentified and unaccounted-for uniformed cop photographed near

the fence on the so-called ďGrassy Knoll.Ē Iím not saying Badge

Man is real or who or what Badge Man worked for or represented.

Iím saying There Are Four Lights.

Itís easy to brand film director Oliver Stone as a nut. He, in

fact, makes it easy and, so far as I can tell, has made a kind

of franchise business of being one of Americaís most famous

nuts. We cannot, however, dismiss the manís genius. It is

precisely that genius that makes his film work and political

propaganda so wickedly effective and, thus, Stone so much larger

than life that he seems to infuriate, well, everyone.e.

Whether you love it or loathe it, Stoneís 1991 classic, JFK, is

a masterpiece, a tour de force of filmmaking. Critics have

labeled it a propaganda film, and I agree, but that hardly makes

it any less brilliant. JFK is, hands down, my favorite film. I

actually tend to think of it as a horror film, one more

devastatingly nightmare-inducing than even the best Freddie

Kruger or Jason film. It was the scariest movie Iíd ever seen

because I walked into the theatre as one person and left as

another. I walked in thinking and believing one way and walked

out terribly shaken and disturbed. Which is not to say Oswald

was not the lone gunman, sure, okay, frame 313 notwithstanding,

Iím willing to be persuaded. The truth or false of Stoneís film

is rather beside the point. I believe the point of the film was

to raise the question, a question of what really happened fifty

years ago, and to elevate it beyond the cult of conspiracy buffs

and into the public mainstream.

This JFK most certainly did, angering and enraging just enough

people to actually prompt Congress to release more information

about the assassination, though not enough to put any of it into

any better context. Stone himself does not claim his version of

events (actually his versions; JFK doesnít promote a single

conspiracy theory but shines a light on them all) is any truer

than the Warren Commission.

What JFK is, however, is one hell of a movie with superb

performances from the first frame to the last. A procedural

drama that deftly and entertainingly winds its way through the

maze of conspiracy theories and colorfully bizarre characters

the vast majority of the American people, so comfortable with

the Oswald story, arenít even aware of. This movie frightened me

to pieces, not because it was true but because I, like hundreds

of millions of others, really hadnít thought a lot about the

assassination or asked any questions at all about it. Both were

impossible to do after Iíd seen that film, a film that left me

sitting in the theater, left side near the front, shaken and

deeply disturbed while its credits rolled over John Williamsí

deeply moving, somber and disturbing score.

It was, I believe, a film a little before its time. Iím unsure

in this cynical age if JFK would have been nearly as

controversial in 2013 as it was in 1991. Stone is accused of

undermining American trust in our national institutions, which

is laughable considering an American president took us into a

desert war under knowingly false pretenses. Haters tend to miss

the forest for the trees, accusing Stone of manipulating if not

outright brainwashing Americans, when brainwashing Americans is

what Google, Facebook, and virtually all news media and

advertising do twenty-four hours per day. The government lies to

us all the time, donít blame Oliver Stone for that. All of his

critics miss the point of the true power of his brilliant

masterpiece: it changed a nation. It forced an act of Congress.

It got the planet talking about the assassination again. Name me

five other American films in the history of cinema that did

that.

Nuts: Costner and Stone.

JFK II

Stoneís subsequent biopic, Nixon, was flawed only in that it

was, of course, compared to JFK. Nixon was an entirely different

picture, but we ponied up our six bucks expecting JFK II and

walked away disappointed, missing the point that Nixon was an

amazing film. It was so amazing that, after the first fifteen

minutes or so, I actually starting buying Sir Anthony Hopkins as

the 37th president, a man he looked and sounded nothing like,

but one he channeled to sublime perfection. Nixon echoed JFK

only at points that, yes, enraged critics, where Stone

speculated Nixon may have been warned of the assassination in

advance (Nixon was meeting with mysterious Texas oil men and,

apparently, shadows Cuban-types in Dallas the day before. Stone

has him reporting these men to FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover,

whom conspiracists also speculate was aware of some plot against

the president but chose to do nothing). Stoneís Nixon also

battles JFK assassination demons concerning Track II (which may

or may not have evolved into or contained Operation Mongoose, a

planned second invasion of Cuba by displaced Cuban nationals),

an initiative set up under President Dwight D. Eisenhower but

run out of Nixonís office. It is this covert paramilitary squad

(and its mob connections) that haunt Stoneís Nixon throughout

the film, leading to the presidentís idle speculation that it

was this asset, designed to assassinate Castro, which was

somehow turned back on Kennedy--a prevailing conspiracy theory

fueled by the governmentís refusal to release the assassination

documents. Critics scream for Stoneís head over Stoneís

allegation, in Nixon, that the legendary 18-minute gap in the

Nixon Tapes contain those musings over the Kennedy

assassination. Nixon, after all, left far more personally

damaging recordings intact.

I leave open the absolute possibility that Iím just having a

little conspiracy fun, here, and that Lee Harvey Oswald was

indeed a troubled ex-marine whose fifteen minutes of fame as a

local rabble-rouser had been up for some time and who simply

wanted attention and got it by a million-to-one shot from a

bolt-action piece of crap rifle with a misaligned site. For the

record: Iíve fired rifles like that and recycling that thing is

a real pain requiring more time than existed between the second

and third shots at Kennedyís motorcade; and Iím talking just

cycling the weapon, not even aiming. I was not in a speed

contest nor was I as nervous as any gunman taking aim at a U.S.

president undoubtedly would have been. Were I in a contest of

speed rather than a contest of accuracy (ha! With that rifle),

Iíd have chosen another weapon. If youíve never handled a weapon

like this, I understand the average citizenís scoffing,

considering how conditioned we now are with rapid-firing weapons

in movies and on TV. The bolt on these rifles is heavy and has

to be manually lifted, yanked back, and shoved back into its

position, which requires at least a couple of seconds of even

the best marksmen, who would then have to re-set his sighting

because the idiotic bolt-cycling on the rifle completely ruins

his aim.

Itís also possible Rose Mary Woods, President Nixonís secretary,

did exactly what she said she did, and accidentally erased the

Dictaphone belt while transcribing boring chatter about how the

Mets were doing that year. Withholding critical records for no

reason I can think of only gives credence to the Bogeyman

stories.

By the way, Roger Donaldsonís brilliant 13 Days, a

low-budget yakfest about the Cuban Missile Crisis, lends quiet

credence to Stoneís JFK in that it depicts, to whatever level of

accuracy, the prickly relationship Kennedy had with his military

chiefs, including going around them to personal order a young

pilot to lie to them. The bullying

from the joint chiefs, most especially from a tad over-the-top

mustache-twirling Air Force Chief of Staff General Curtis LeMay,

lays grave credibility to Stoneís film. I have no way of knowing if

13 Days is any

more or less true than Stoneís JFK, but the quiet, sad, subtext

of 13 Days is the audience knowing, for a fact, what awaits the

young president beyond the filmís end credits.

Christopher J. Priest

2 December 2013

Home | Blog | Projects | Comics | Rants | Music | Video | Christian Site | Contact

Film Trailer and Stills from JFK

Copyright © 1991 Canal+ / Warner Bros. All Rights Reserved.

Unless Otherwise Noted, Text Copyright © 2013 Lamercie Park. All Rights Reserved.

TOP OF PAGE