Jesus Christ! The fucking gimp finds something useful to do

in the fucking brace you made her! Do you think you could treat

being Johnny—always struggling to fashion a thought?! Every

fucking night I, that could cut a throat but sleep the sleep of

the just, spend six fucking wakings trying to find a piss pot

with my dribble, and wondering when I got to be so old.

(He throws the swatches down onto Doc.)

Pick a fucking swatch for a spit rag, use the others for masks,

and go about your fucking business!

I ain’t learning a new Doc’s quirks.

—Al Swearengen,

Unauthorized Cinnamon

I am not a man.

I can write men, I can invent men, men of valor and purpose and

resolve. Unbendable, unbreakable men who stare down adversity

and challenge injustice. These fictional men are the reason we

go to the movies, why we buy books and, yes, comics. The hero

fantasy is likely the most basic human beings have as men

and women alike gravitate toward powerful figures; powerful in

courage and resolve if not in physical or “super” strength. The

real world is very cruel in the sense that men like this are an

extreme rarity and they are usually killed. Our national role

models are a bunch of simpering, whiny mama’s boys in Washington

who are about as rugged as Frazier Crane and who invoke a veneer

of self-righteousness and call it courage. These men always have

ulterior motives and their pretense to courage exists only to

manipulate people.

Deadwood’s Seth Bullock is a real man, which is what makes

Timothy Olyphant’s portrayal so watchable. It is also what makes

Justified, Olyphant’s subsequent Elmore Leonard-produced

vehicle, so disappointing. I had hoped Justified would be Seth

Bullock In 2011. But Raylan Givens, Olyphant’s Justified U.S.

Marshal, is nothing at all like the brooding, disturbed Sheriff

Bullock of Deadwood; which is a crying shame. I don’t think

Givens is more entertaining than Bullock, though he has more

dimension. A character like Bullock, mean, short-tempered and

evidently self-loathing, couldn’t possibly hold the center of a

regular series though he pretends to, here. Truth is, there are

many episodes where Bullock hardly shows up and barely speaks.

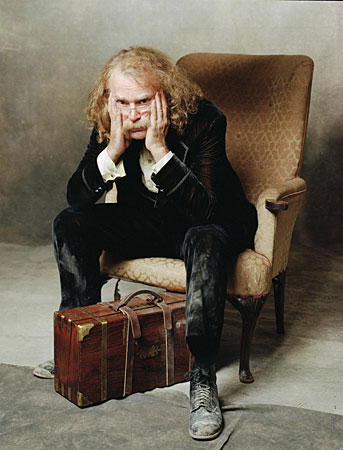

Olyphant receives top billing in every episode, while Ian McShane, who plays Bullock’s scenery-chewing foil Al Swearengen,

often recites the equivalent of the King James Bible in most

episodes, yet his name comes in second.

McShane’s Swearengen drives the story. Deadwood could likely be

subtitled "The Education of Seth Bullock,” as show creator and

TV scripting demigod David Milch has composed a plot so densely

layered the show threatens to be much more intelligent than its

audience. I learned almost nothing about the story the first

time through, where I was frequently confused and lost in the

twists through the alleys of Milch’s mind. Having now completed

a second viewing (and with the aid of subtitles and a pause

button), I had a much richer experience. While presented as the

heavy, Swearengen is actually an anti-hero. Bullock is only at

center in the minds of the audience who surely expect the

sheriff to eventually be the good guy. Given top billing, and

rivaled by no other character who walks or talks so squarely, it

is a reasonable assumption that Olyphant/Bullock will hold the

center. Milch relies on that expectation to spin his warped

tale. The overall story is never about Bullock but about

Swearengen. Bullock is not the center but barely a spoke on

Swearengen’s wheel. He is not half as intelligent or as

thoughtful or, in the end, as self-sacrificing as Swearengen, a

brilliant character who masks his heroics in self-interest (or,

is it the other way around?). His actions are heroic nonetheless

because, in pursuit of his own interests, Swearengen saves the

muddy, dumpy little camp he all but founded. While retaining his

top billing, Bullock is, by season three, shunted off as just

another cast member while Swearengen is in practically every

scene.

Swearengen’s total domination of Bullock begins with the second

season premiere, where Swearengen picks a fight with Bullock to,

ostensibly, wean Bullock from a distracting and potentially

destructive affair with Mrs. Alma Garet, widow of a rich idiot

from New York whom Swearengen’s henchman helped down off a

mountain. The camp’s very existence is imperiled by the looming

threat of a wealthy industrialist, played to villainous

perfection by Gerald McRaney, and Swearengen needs Bullock—the

square-jaw face of the camp—to keep his sainted image

untarnished and get focused on the gathering storm. The ensuing

battle is quick, brutal, and appropriately epic, and we wait

patiently for the following 21 episodes for another. It never

comes.

Milch’s overly languid storytelling pace is enormously

frustrating. He wiles away entire episodes with length

soliloquys—brilliantly written, but we want some action. There

is always the threat of action, but Deadwood is not an action

show, not even a Western by traditional standards. Not one

single Main Street gunfight, precious little fisticuffs, and a

maudlin over-abundance of heinous misogyny which left me

cringing as I wondered how accurate that was: were women,

prostitutes in specific, really treated that badly?

The Effing Bard: Effing Milch.

Effing Cooksuckers

Anyone familiar with the series can tell you Deadwood is written

in an often-perplexing “Profane Shakespeare.” Creator David

Milch’s inventive uses of the F-word is likely unparalleled in

TV history, though it makes me wonder if people actually talked

that way; I’d always assumed that word to be a relatively modern

invention. It is, in the end, this wonderfully profane poetry

that dazzles the most. Finger on the pause and subtitle buttons,

I remained enthralled with the lingo from start to finish, even

as I was aghast at how racist and misogynist the accepted norms

were.

The real, historical Seth Bullock was a Republican who lost the

sheriff’s election in a landslide. Like our Republicans today,

Bullock refused to accept the election’s outcome and did not

surrender power for weeks or months after while challenging the

election in court. In a commentary, Milch see his fictional

Bullock as something of a lost boy, a man who rises, every day,

wishing he could beat the crap out of his father. In Swearengen,

Bullock finds some semblance of a father figure, though he never

acknowledges it. The two never become friends, but they bond

over their common enemy of Hurst. The fictional Bullock is,

however, rendered largely irrelevant past season two’s terrific

2-part opener, which lends an air of frustration to the viewer

who returns, episode after episode, looking for a story actually

about Bullock, or in which Bullock actually moves the narrative.

He does not. He is an extra, a face in the crowd. He is,

essentially, the face of the ragged camp—it’s alleged

champion—but he fights no battles, saves no lives. He briefly

arrests Hurst and we think, finally, we’re getting somewhere,

but even that is a wrong tactical move that only makes things

exponentially worse.

Based on the DVD extras, I am assuming Milch and company were

tailoring their narrative more or less toward the historical

facts. This created an ultimately unsatisfying and frustrating

experience because we’ve all been conditioned to expect certain

things, the hero saving the day among them. But Bullock simply

isn’t that smart. He comes across as wiser than he actually is

mainly because he tends to isolate and saunter around the camp

in an amazing, fun-to-watch pimp roll designed specifically to

shoo people away from him. Swearengen, on the other hand,

tolerates a great many fools and, therefore, is in tune with the

heartbeat of the people Bullock ignores as he saunters past,

steely-eyed.

After a strong start as Swearengen’s rival, Powers Boothe is

completely wasted in season three, making only sparse

appearances in indecipherable scenes. Prior to Hurst’s arrival,

Boothe’s character was the most demonstrably evil guy in the

show. Hurst quickly neuters him, which I suppose was designed to

define Hurst, but you don’t have an actor like Boothe on payroll

and just let him fade away.

This is, however, the mad genius of Milch. Milch may write the

same way I do, in a sloppy intuitive fashion as opposed to the

strict outlining we all learned in school. The difference seems

to be, I will tend to work far enough ahead of production to

irritate my editors with multiple rewrites as I learn more about

my characters and their motives. Based upon the

behind-the-scenes extras, Milch seemed to be winging it; making

it up as they went and writing right up to shooting if not

beyond (there were literally no scripts during Milch’s final

days on NYPD Blue; Milch just showed up on the set (eventually)

and improvised everything. I don’t know if that’s what he did on

Deadwood, but the unevenness of the narrative and the deeply

unsatisfying third season where Milch all but sidelines the lead

character and hobbles the great Powers Boothe while languishing

lonnnnnng scenes on characters we don’t give a crap about (the

theater troop?!?), suggests he may have simply been winging it.

This is no crime, but I can’t help but wonder what might have

been had Milch been far enough ahead of schedule to go back and

polish previous episodes before they were shot.

Even

When It Bores

Even

When It Bores

"So, including last night, that's three fucking damage incidents

that didn't kill you. Pain or damage don't end the world or

despair or fucking beatings. The world ends when you're dead.

Until then, you got more punishment in store. Stand it like a

man, and give some back." – Al Swearengen

Virtually every character in Deadwood turns in amazing

performances, so going on and on about each of them will only

give me carpal tunnel, but I deeply enjoyed Robin Weigert’s

“Calamity” Jane, a performance that shattered the myth of Jane

having been some kind of superwoman gunslinger. Weigert’s’s Jane

is a terribly tragic, unloved, obnoxious, broken alcoholic who

is ultimately saved by Kim Dickens’s quixotic and compelling

whorehouse madam Joanie Stubbs. Beautiful and terribly insecure,

Joanie nonetheless moves through Milch’s passion play propping

up and reassuring others while desperately trying to avoid

Boothe’s Cy Tolliver, who is obviously in love with her; love

being played for weakness, here, and thus provoking Tolliver’s

abusive nature.

Keith Carradine threatens to upstage everybody as James Butler

“Wild Bill” Hickok. Early into the series, it appears that

Caradine will take a central spot alongside Olyphant’s Bullock,

and we’re off to the races with a pair of fearless gunslingers

at center stage. Of course, this is not what Deadwood is about,

so Milch abruptly interrupts that thinking. But, boy, was

Caradine good.

This is a terribly uneven series, but the brilliance of the

writing remains constant even though the third-season slog of episodes

seemingly phoned in from some off-path motel Milch might have

been staying in. Even when it bores, Deadwood is brilliant, due

largely to Milch’s poetry (and, for all I know, the legion of

writing assistants who assist and embellish). Regular viewers of

network TV (which is beyond awful) simply won’t “get” Deadwood.

It moves way too slow, the dialogue verges on indecipherable,

the hero is a borderline idiot, there’s too many characters to

keep track of, and there are few if any satisfying moments--

Bullock kicking the crap out of Hurst’s sadomasochistic advance

man being one of them. Warned that Hurst will seek retribution,

Bullock snarls in gleefully satisfying hero-villain mix (in my

paraphrase), “You

draw a map and let him know where to find me. And tell him...

I’ll be waiting.”

Huzzah, kids.

Christopher J. Priest

12 November 2013

Home | Blog | Projects | Comics | Rants | Music | Video | Christian Site | Contact

Film Trailer and Stills from Deadwood

Copyright © 2013 HBO. All Rights Reserved.

Text Copyright © 2013 Lamercie Park. All Rights Reserved.

TOP OF PAGE